Putting an end to the rule of thirds.

This slightly provocative title introduces an article to take stock of the famous rule of thirds. This rule is so poorly described in many tutorials and even in beginners' magazines that many photographers remember that the subject has to be off-centre. The result is unbalanced images, and in the worst cases, the subject has even lost its identity as a subject in favour of a void that occupies the centre of the image.

The subject must be at the centre, unless there is a valid reason to move it off centre.

It's also worth bearing in mind that, although the rule of thirds is often invoked, there are many other rules, each of which corresponds to a specific intention. The photographer will therefore have to choose, from among all these rules of composition, the one that best corresponds to what he wants to say or show in his image.

There is nothing worse than the systematic application of a rule, without reflection on a case-by-case basis.

What is the rule of thirds?

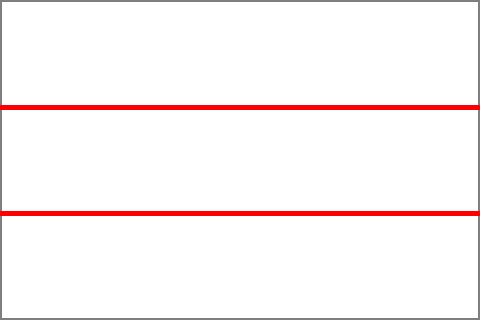

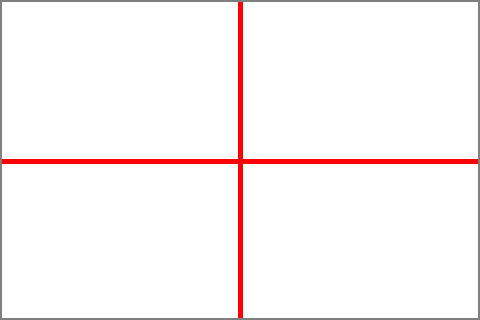

The rule of thirds states that it is advisable to place the subject or the main lines of the image not in the middle of the image but on a third. The image is divided into thirds both vertically and horizontally.

For example, in the case of a landscape, the horizon line should be placed on the upper or lower third of the image. The photographer will therefore have to choose whether to give more prominence to the sky or to show more of the ground.

Division of the frame into three horizontal thirds

Division of the frame into three vertical thirds

Some practical examples of the application of the rule of thirds.

Viaduct at Pélussin (France)

The framing of the photo above does not respect the rule of thirds: the horizon line has been placed halfway up the image.

This other framing conforms to the rule of thirds: the top of the viaduct is in the top third of the image.

The sky, which is not the focus of this image, is reduced to the ground profile, which is rich in detail.

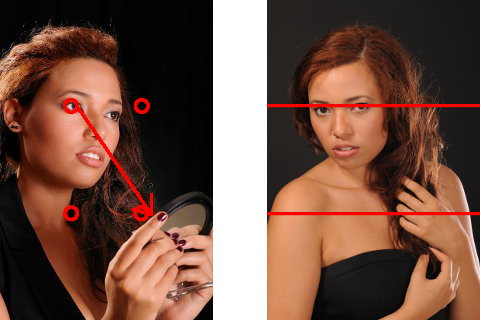

Julie eating an apple

In the portrait on the left, the model's face has been placed roughly in the middle of the image, while in the portrait on the right the face is much closer

to the top third. This second image is more balanced: less space is lost above the portrait.

The strong points: where it all goes wrong.

The intersections of the lines of thirds are what we call the strong points of the image.

Since it is recommended to align the lines of the image with the lines of thirds, we could deduce that it is even more recommended to place the subject at the intersection of a vertical line of thirds and a horizontal line of thirds, in other words on one of the strong points.

That's where the mistake lies: the subject is almost always centred horizontally. Most of the time, applying the rule of thirds only in the vertical direction is sufficient, as the examples above show: the horizon line on one of the thirds or, in the case of a close-up portrait, the eyes are placed in the top third of the image.

Stubbornly placing the subject on one of the strong points can only unbalance the image. Alternatively, something should be placed on another of the focal points (ideally the opposite focal point) so that the image does not appear unbalanced. This something must, of course, be of lesser importance than the main subject, but it must not be insignificant.

Proper use of the rule of thirds.

The rule of thirds on a landscape.

Véranne village (France)

The subject is undoubtedly the village: it is therefore centred in the image. However, the image is roughly divided into three horizontal bands, each

occupying a third of the height: the sky, the village and finally the fields with the trees in the foreground: the rule of thirds is followed.

The bell tower (which is an element of the subject, but nothing more) has been placed at a strong point in the image, while a large house is placed at a second

strong point, to balance the photo.

The rule of thirds on a portrait.

In the portrait on the left, the model's right eye has been placed on one of the strong points of the image, and the mirror, located near a second strong point,

balances the image.

But is it the eye or the mirror that is the subject of the photograph?

Neither: this photo shows a woman looking at herself in a mirror: the real subject is her gaze, and it is right at the centre of the image.

If we had wanted to make the face the subject of the image, we would have framed it as in the portrait on the right.

In the photo on the right, the subject is clearly the young woman. The rule of thirds has been followed: the eyes are on the top third. But the subject (the face) has not been placed on a strong point, which would have unbalanced the photo.

What does the horizontal decentring of the subject mean?

In some cases, however, it is desirable to move the subject off-centre, even horizontally. This creates an imbalance that suggests something unstable: you feel that things cannot remain in this state for very long and that the situation will change.

Images with an off-centre subject therefore suggest dynamics.

When the subject also has a dynamic characteristic, it's a good idea to shift the focus to one of the strong points of the image. This might be the case, for example, with a sportsman in action, an animal ready to pounce, a vehicle on the move, etc.

The raft of the Medusa (Gericault)

The unstable situation on this raft has been accentuated by the fact that all the elements that catch the eye are off-centre (the sail, the sailor waving, etc.).

there is nothing of importance in the centre of the painting, and the painter has used numerous diagonals to reinforce the impression of instability.

The mad scientist

Here's an image showing a rather zany laboratory, in which a machine appears to be under pressure, ready to explode. The impression of instability is reinforced

by the fact that there is nothing in the middle of the image, while the operator's face and the machine are each on one of the strong points of the image.

What does the centred subject mean?

In contrast, the subject in the centre of the image suggests a certain stability, a lasting situation that is unlikely to change in the future.

In painting, kings are almost always depicted in the centre of the canvas. If courtiers are depicted, they are arranged around them. A painter who disregarded this rule would undoubtedly have run into trouble, because it means that the king is in an unstable position.

The King drinks, a painting by Jacob Jordaens (1640)

Even in a state of inebriation, the king is depicted at the centre of the canvas.

(Note: there are other versions of this table in which the king is not centred)

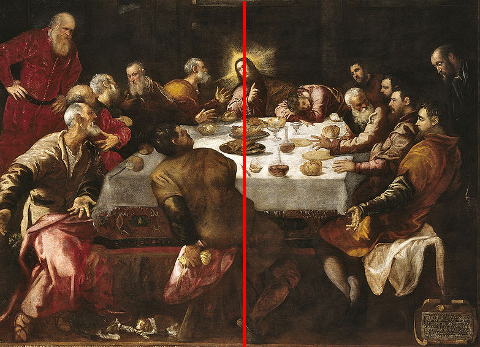

Last Supper (a painting of Tintoretto)

The face of Christ is perfectly in the centre of the canvas in the horizontal direction..

Cat sleeping on a cushion

The cat will be placed in the middle of the image to emphasise the fact that the animal does not intend to leave this position (cat character).

The rule of diagonals.

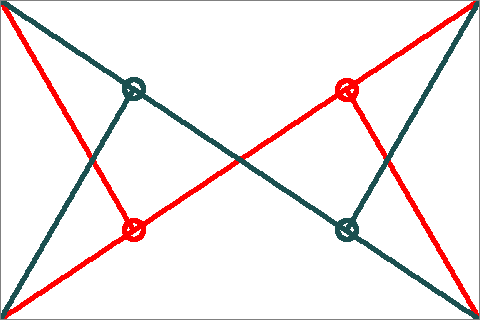

Another rule of composition is to draw one of the diagonals and the perpendiculars to the opposite corners. Of course, this works with the two diagonals. The strong points obtained with this method are very similar to those obtained with the rule of thirds.

The diagonal rule is more complex to use when shooting. It can be used for cropping in post-processing.

Viaduct at Pélussin (France)

The framing was done according to the rule of diagonals: the slope of the land on the right of the bridge follows the diagonal,

and the main arch is in line with the strong point on the left.

In this second photo of the viaduct, composition that scrupulously respected the strong points of the rule of thirds would have produced something a little different.

Ruins of a fortified castle near Vienne (France)

Here too, the composition has been done according to the rule of diagonals: the slope of the hill follows the diagonal and the castle is situated approximately

on one of the strong points of the image.

Conclusion.

- The rule of thirds, which is considered a universal rule, is not: there are many other rules to help in the composition of an image. The photographer must first determine what he or she wants to say, what impression the photo should convey. He can then use the most appropriate compositional rule.

- Under no circumstances does the rule of thirds require the subject to be placed on one of the strong points of the image, i.e. off-centre horizontally.

- The fact that there are several rules that don't give the same results doesn't mean that you can do without the rules: an image that doesn't obey any compositional rules will probably be difficult to read and is unlikely to be pleasing to the eye.

If you liked this page, share it on your favorite network :